Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Inguinal Hernia

What is an inguinal hernia?

A hernia happens when a part of the abdomen pushes through an opening in the abdominal wall. An inguinal hernia is a hernia that occurs in the groin area.

Inguinal hernias occur in 7 percent of boys and almost 1 percent of girls. In children born prematurely, up to 25 percent will have inguinal hernias. Inguinal hernias may occur on either side of the groin, but they are more frequent on the right side and sometimes occur on both sides.

In adults, hernias typically occur after the abdominal wall becomes weak. Unlike adults, infants, children, or teenagers with hernias are born with an opening in the abdominal wall that failed to close during pregnancy, causing the hernia to form.

An inguinal hernia will be apparent if there is a soft bulge in either the inguinal area (the crease between the abdomen and the top of the leg) or in the scrotum.

Symptoms & Causes

What causes inguinal hernias in children?

In male fetuses, the testicles develop in the back of the abdomen just below the kidney. As the fetus develops, the testicle descends from this location into the scrotum, pulling a sac-like extension of the lining of the abdomen with it. This sac surrounds the testicle into adult life, but the connection to the abdomen generally entirely resolves (goes away). If the abdominal wall does not fully close, a hernia will result.

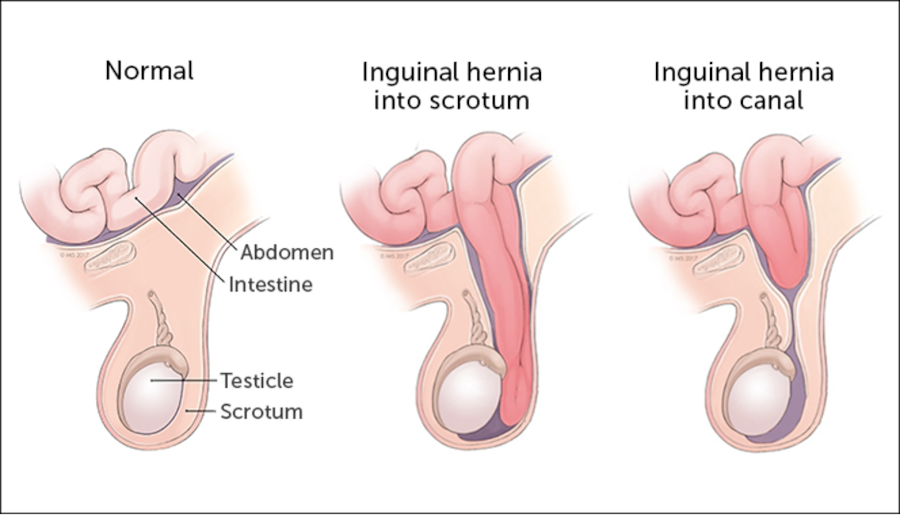

There are two kinds of inguinal hernias:

- An inguinal hernia into canal extends from the abdomen into the inguinal canal.

- An inguinal hernia into scrotum extends all the way from the abdomen into the scrotum and the sac surrounding the testicle.

Although girls do not have testicles, they do have an inguinal canal, so they can develop hernias as well. It is often the fallopian tube and ovary that fall into the hernia sac.

Inguinal hernias always have an open space but are only noticeable when there are contents from the abdominal cavity within the sac. In infants and children, a hernia may not be apparent if the opening in the abdominal wall is too narrow to allow contents from the abdominal cavity to be pushed from the abdomen into the sac.

As a child grows and develops, the abdominal wall becomes stronger and can push contents through the opening into the sac. Often this makes the opening larger.

Some factors place children at higher risk for inguinal hernias, such as:

- Premature birth

- Undescended testicles

- Family history of hernias

- Cystic fibrosis

- Hip dysplasia

- Urethral abnormalities

Occasionally, in both boys and girls, the loop of intestine that protrudes through a hernia may become stuck and cannot return to the abdominal cavity. If the intestinal loop cannot be pushed back into the abdominal cavity, that section of intestine may lose its blood supply. A good blood supply is necessary for the intestine to be healthy and function properly.

What are the symptoms of an inguinal hernia?

Inguinal hernias appear as a bulge or swelling in the groin or scrotum. The swelling may be more noticeable when your baby cries and may get smaller or go away when your baby relaxes. If your doctor pushes on this bulge when your child is calm and lying down, the hernia will usually look smaller or normal as the contents of the sac go back into the abdomen.

If the hernia is not reducible (does not get smaller with gentle pressure), then the loop of intestine may be too swollen to return through the opening in the abdominal wall. In this case, your child may need urgent surgery to prevent damage to the intestine.

Call 911 or seek immediate emergency care if your child has an inguinal hernia and any of the following symptoms:

- Green vomit

- A hard lump in the groin

- Inconsolable crying

Diagnosis & Treatments

How are inguinal hernias diagnosed?

Your child’s doctor can diagnose an inguinal hernia by a physical examination. They will determine if the hernia is reducible (can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity) or not. They may order abdominal X-rays or an ultrasound to examine the intestine more closely, especially if the hernia is not reducible.

What are the treatment options for inguinal hernias?

Most of the time, an inguinal hernia requires surgery to prevent damage to the intestines or other abdominal tissues.

Your child’s doctor will recommend treatment based on your child’s age, health, medical history, and type of hernia.

- If your child is a newborn, your doctor may recommend delaying surgery until they’ve grown larger and stronger.

- Toddlers and older children with inguinal hernias typically have surgery soon after the hernia is discovered.

During a hernia operation, your child will be placed under anesthesia. The surgeon will make a small incision near the hernia. They will then move the abdominal tissue back into the abdominal cavity and stitch the abdominal muscles together.

A hernia operation is usually fairly simple. Your child may be able to go home on the same day as the operation.

Once the hernia is closed, it is unlikely it will reoccur.

How we care for inguinal hernias

The Department of Surgery at Boston Children’s Hospital provides general and specialized surgical services to infants and children with inguinal hernias. Our team has special expertise in the treatment of inguinal hernias and will collaborate with you to design a care plan appropriate for your child.

Boston Children’s Department of Urology is a world leader in pediatric urology, offering specialized care for a wide range of urologic disorders in children and adolescents. Our team has special expertise in the treatment of inguinal hernias.